Polyester

Definition

Polyester is the common name given to fabric and textiles made from fibres of polyethylene terephthalate (PET). As a derivative of the world’s most commonly produced fossil-based plastic, polyester can be found in a wide variety of applications but is most frequently used to produce fabric and yarns, accounting for over 50% of global textiles production.1

Production

Following its invention in the early twentieth century, polyester’s popularity grew steadily as an affordable and easily produced textile that is durable, crease resistant and colourfast. In the 1940s American chemical company DuPont established the commercial rights for polyester production and began to develop it for the mass market, alongside other emerging synthetic fibres such as nylon and elastane.

Polyester is made from a combination of refined crude oil and synthetic chemicals such as ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid. Today, its manufacture accounts for around 340 million barrels of oil extraction every year2, which is processed or ‘cracked’ in refineries to break down molecules into the essential ingredients for plastic using heat, pressure and chemical processing. To create the polyester fibres used in garments, plastic PET pellets are melted and extruded to form thin filaments, which are drawn out to improve their strength at the molecular level. These fibres are then spun into yarns either in isolation or in combination with other material blends prior to weaving.

Polyethylene terephthalate pellets are melted, extruded and spun into polyester yarn. Image: Olso

Dyeing polyester yarns is generally less energy intensive than dyeing cotton, but the processes often use carcinogenic compounds or heavy metals such as lead or cadmium, which can potentially be discharged into wastewater in the environment. Further processing such as adding water repellency may involve potentially carcinogenic chemicals such as PFAs (poly-fluorinated alkyl substances), which are notoriously persistent in the environment and have been identified in the ecosystems of remote or uninhabited regions across the globe.3

Unlike cotton production, polyester is not constrained to certain climatic regions, but it is mostly manufactured in the USA, closely followed by China, with as few as three companies responsible for nearly 50% of global output. Although polyester manufacturing has a lower environmental impact on water and land use compared to cotton, its manufacturing production and end-of-life disposal is energy intensive and highly polluting.

Approximately 85% of polyester is currently made using virgin raw materials,4 although the proportion of polyester made from recycled PET (RPET) has risen significantly in recent years. Each metric tonne of recycled material is estimated to save the equivalent of two years’ household energy consumption,5 so although not without its own problems, recycled source material has the capacity to dramatically lower the carbon footprint of polyester and reduce additional chemical inputs and new oil extraction.

In Use

The annual global production use of polyester has increased from 5.2 million tons in 1980 to 71 million tons in 2023.6 Part of this rise is due to the advent of the modern sportswear market. Polyester’s ability to resist water absorption and to blend with other fibres makes it a dominant fabric in modern sports and outdoor wear, with innovations in weave and construction technology helping to improve comfort, performance and fit.

Polyester’s versatility accounts for over 70% of all growth in textiles demand between 1980 and 2014,7 and has helped fuel the explosion of fast fashion, with clothing consumption doubling in the 15 years to 2020.8 Climate action charity WRAP estimates that the volume of new garments consumed in the UK will increase from 1.66 million tonnes in 2018 to as much as 2.37 million tonnes by 2030.

Polyester has become a dominant fabric in sports, fast fashion and outdoor wear. Image: Olso

While organisations such as Textile Exchange (a global non-profit organisation) are calling on producers to commit to sourcing 45% to 100% of their polyester from recycled sources, industry projections suggest that this shift in demand for recycled polyester (RPET) will soon outstrip supply and that even without this increased demand for RPET textiles, the current reliance on used PET bottles to create RPET is insufficient to meet the projected demand for the drinks industry alone.9

Alongside the very visible pollution caused by plastics in our seas and rivers, domestic laundry of polyester is also now known to release its fibres into the environment on a microscopic level, with estimates suggesting that half a million tonnes of microfibres (equivalent to 50 billion plastic bottles) are released into the ocean each year.10 While non-profit organisations and charities use large-scale booms and traps to intercept and collect sea plastic for recycling, an increasing number of domestic devices are available to prevent the microfibres being released into wastewater from washing machines. Although concerns remain around the lack of standardised certification in this emerging market,11 France has become the first country to take legislative steps on this issue, announcing the introduction of mandatory filters on washing machines from 2025.12

End-of-life

Currently the infrastructure and technology required to recycle polyester garments in a truly circular manner remains limited. Virtually all recycled polyester found in today’s textiles is sourced from recycled PET drinks bottles rather than used polyester garments, and across the industry less than 1% of clothing textiles are thought to be recycled into new clothes.

Although it is increasingly easy to source 100% recycled polyester garments, in reality this process only defers the journey of the material to landfill or incineration. Many critics argue that PET drink containers should remain in a closed loop system that better allows for their recycling back into new bottles, rather than being diverted into an alternative linear process that results in the material then being discarded as waste.13

Globally, around 12% of waste fabric will avoid landfill by being down-cycled into lower-value items such as insulation, stuffing or industrial fabrics, but recycling fabric again from these applications is problematic so they are usually discarded. The UK generates one of the highest levels of textiles waste in Europe, accounting for about 3 kg per person per year. Of this, approximately 300,000 tonnes are disposed of in household waste, resulting in around 20% going straight to landfill and the rest being incinerated for energy.14

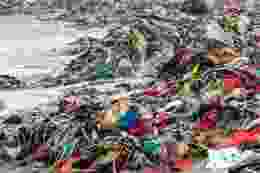

Although charity donations and recycling collections are widely used in the UK, typically only 20% of these are resold as secondhand or preloved items, with the majority exported abroad, according to a 2023 report by nonprofit foundation theguardian.org which explored the impact of used clothing exports to Ghana, the world’s biggest importer of used clothing.15 In 2021 Ghana received about 15m items a week,16 4.13% of the global total of that year’s imported used clothing. While much of this is resold or reconstructed into new garments, approximately 40% is of such poor quality that it is incinerated or dumped in informal landfills around the capital Accra,17 where the city’s Korle Lagoon has been named one of the most polluted waterways on the planet.18

Discarded secondhand clothes cover the beach in the coastal fishing community of Jamestown in Accra, the capital of Ghana. Photograph: Muntaka Chasant/Shutterstock

Similar issues occur around the world. More than half of Chile’s total import of used clothing19 (just over 3% of global used clothing imports) is claimed to be illegally dumped at just one single site in the Atacama Desert.20

As polyester carries very little potential to biodegrade, it creates long-term environmental issues when landfilled – releasing methane gas and harmful chemicals into soils and groundwater. Despite efforts by importing nations to tackle illegal landfill through regulation and policing, without legislation to reduce and reuse the volume of polyester generated by the global textiles industry, the effect of such moves will likely displace the problem to other importing countries.

Although the recycling of PET bottles is well established, effective fibre-to-fibre recycling for polyester remains expensive and underdeveloped, especially for blended fibres and fabrics, where it is difficult to control the resulting yarns. Like PET bottles, if polyester can be easily separated by colour and material, it can then be recycled by two basic processes:

Mechanical recycling shreds polyester and re-processes it back into new fibres with virgin material added to compensate for the loss in fibre quality. Additional dyeing or bleaching processes may be required but if materials have been separated by colour this can be avoided.

Chemical recycling returns fibres back to their original molecular building blocks, or monomers, by entirely dissolving the fibre structure with chemicals to break their molecular bonds. Pilot versions of this process can even be used on blended fabrics such as polycotton.21

In recent years a new market for bio-based alternatives to polyester has emerged, with innovative fashion brands such as Pangaia and Ganni increasingly using bioplastic or cellulose fabrics to replace fossil-based fibres. Materials such as EVO® and CLARUS® are made from plants or post-industrial waste that reduce demand on water resources and fossil-based fertilisers, while simultaneously cutting demand for new oil extraction.

EPR (Extended Producer Responsibility) schemes are also seen as effective legislative policies to reduce textile waste and improve recycling. EPR requires manufacturers to take financial or physical responsibility for the post-consumer stage of a product’s life cycle by applying economic disincentives such as landfill taxes or encouraging investment into recycling technologies.

Similar to established schemes in France and Sweden, the UK government has indicated that an EPR levy of 1 pence against each garment sale in the UK could raise £35 million towards investment in textile recycling infrastructure,22 and climate action NGOs such as WRAP campaign to support this industry transition through initiatives such as Textiles 2030, that promote circular business models and accelerate commercial fibre-to-fibre recycling.