Household Chemicals

Definition

Household chemicals account for many of the ingredients found in single-use products and consumer goods that are manufactured to assist in domestic maintenance, cleaning and general hygiene tasks.

Production

The most visible use of household chemicals can be encountered in cleaning products – from soaps and laundry products to disinfectants and dishwashing liquids. They can be used in daily life with little consideration to their environmental impact, whether from manufacturing, use or disposal. The majority of household cleaners derive their main ingredients from crude oil or petroleum, and an increasing demand for petrochemicals means this sector is projected to account for around half of global oil industry growth by 2050.1

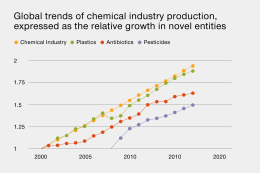

The rapid expansion in chemical manufacturing during the later twentieth century played a significant role in a wider process of human planetary impact, often referred to as the Great Acceleration. Estimates for the number of different synthetic chemicals that humans have created during this period range from 25,000 to 140,000,2 and the UN has indicated that the production capacity of the global chemical industry continued to almost double between 2000 and 2017.3

Source: American Chemical Society / UN Environment Programme

Household chemicals are a significant part of this global industry, with, for instance, traditional powdered detergent alone still accounting for an annual 14 million metric tonnes of chemical manufacturing per year.4 The European Environment Agency estimates that over 350 million tonnes of chemicals are consumed in Europe each year with 36 % classified as hazardous to the environment,5 much of which are the ingredients of household cleaning products that are typically released into the environment through wastewater sewage systems. Although wastewater treatments are designed to break down contaminants through physical, chemical or biological methods, they are often unable to remove all chemicals, meaning many remain in sewage or are released untreated into natural watercourses.6

One of the most widely used classes of household chemicals are surfactants, which are designed to dissolve grease and dirt. Surfactants make up the main active ingredient in many household cleaners, although such products also employ a host of additional chemicals, from water softeners and optical brighteners to synthetic fragrances and dyes. As the environmental and health impacts of many chemicals remain unknown, the term ‘emerging contaminants’ has been coined to describe those that have become evident (although still frequently undetected) through newly improved monitoring and analysis techniques. The British Geological Survey, a UK government-funded monitoring agency, defines emerging contaminants as ‘substances which are not yet regulated but may be of environmental or human health concern’.

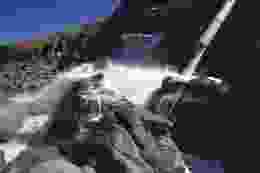

Discharge from the UK Marchon site which produced a range of chemicals for detergents and toiletries and was once the biggest single polluter of the Irish Sea. Photo © Greenpeace / Alan Greig

As part of the global UN environment programme, the Stockholm Convention of 2001 committed nation signatories to remove or severely restrict the use of the most toxic known household chemicals or Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs). Since 2007, EU manufacturers must also introduce new chemicals via the European regulatory body REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals), which places a burden of proof on producers to demonstrate substance safety – although the rules do not apply to chemicals introduced before this date. Although many are now banned (including chemicals that were originally regarded as safe), the nature of existing POPs or ‘forever chemicals’ mean they do not readily break down or degrade, which means their presence continues in the environment – slowly accumulating in plants and animals and across the food chain through a process known as bioaccumulation. Many POPs are known to be carcinogenic and affect the reproductive, nervous and immune systems of both humans and wildlife ecosystems.

In 2003, Monsanto, the largest manufacturer of the notorious forever chemical PCB (polychlorinated biphenyls), paid out more than $700m against discharges and chemical landfills which poisoned inhabitants near a manufacturing plant in Alabama, USA, whilst producing PCBs for household goods such as paints, paper and adhesives. Although now banned by international agreement, it is believed that 1.5 million tonnes of PCBs have been produced globally, with some geographical areas involved in such intensive chemical manufacturing often referred to as ‘sacrifice zones’. While general public awareness of PCB pollution is limited in the UK, a BBC environmental report in 2024 with the Royal Society of Chemistry7 revealed samples around UK chemical landfill sites leaching PCBs into publicly accessible waterways and soils at levels up to 12,000 times higher than background concentrations,8 resulting in one site being referred to as ‘one of the biggest environmental crimes to have occurred in the UK’.9

Meanwhile, in 2025, residents on the French border with Switzerland and Germany were affected by the country’s largest ever ban on drinking tap water due to contamination by forever chemicals leaching into groundwater from a nearby airport.10 The Guardian reported that contaminated sites are also thought to be ‘littered across Europe’, with blood tests on residents of towns in Italy and Belgium showing forever chemical levels well above above EU limits, due to their proximity to multinational chemical plants.11

Although mandatory for chemicals used in food and cosmetics, the disclosure of the precise formulations of household cleaning products are not readily required in the UK. According to the detergents regulations, only categories of ingredient need be listed when they exist in concentrations above 0.2%.12 Ingredient data sheets must be published – often on websites (although not necessarily by the manufacturers) – but the extent of this content need not be comprehensive, and the manner of its presentation remains unregulated. Furthermore, it is an offence to unlawfully disclose fully comprehensive details – the only parties deemed needing to know being medical personnel. For consumers (and even regulators), this can make the process of discovering the exact nature and amount of chemicals in many household products difficult, if not impossible to grasp.

Chemical ingredient data for consumers does not need to be comprehensive. Image © Olso

In Use

Household chemicals will typically linger in the domestic environment as surface residue or airborne particles, but are also frequently disposed of via sinks and drains. Domestic drains connect to a local network of sewers which transport wastewater to treatment works and settlement tanks that are designed to separate solids and water through stirring and gravity. After further biological treatment or disinfection, separated water is returned to rivers and seas, while any solids or sludge is burned, landfilled or recycled as agricultural fertiliser. According to Ofwat (the body responsible for regulating the water and sewerage industry in the UK), 80% or around 3.5 million tonnes of this residue known as ‘biosolids’ is commonly put to use as fertiliser in the UK every year. Although in principle biosolids can be beneficial in returning nutrients to the soil and reducing demand for chemical fertilisers, several countries have banned the practice due to its potential to pollute soils with emerging contaminants and plastic particulates.

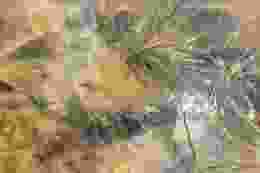

In 2020, environmental investigators Unearthed,13 accessed a government report suggesting that soil treated with biosolids could become ‘unsuitable for agriculture’ due to outdated safety testing methods that overlook contamination from contemporary pollutants including POPs, plastic-derived phthalates and antimicrobial chemicals such as triclosan – non of which are routinely tested for in sewage. The unpublished report concluded that there remain ‘no legal limits to the amount of these chemicals that can be present in landspreading sludge’. Simultaneously in 2020, the UK Environment Agency published a nationwide survey showing that only 16% of national waters achieved the criteria for ‘good ecological status’, with 0% meeting the criteria for ‘good chemical status’ relating to human activity. This was an alarming 97% drop from previous figures which actually unveils that it is only due to improved monitoring techniques that we are beginning to obtain a more accurate picture of the scale and impact of synthetic household chemicals in our water systems.14

UK waterways affected by excessive algal growth caused by high levels of phosphate pollution. Photo © BBC

Among the chemicals or POPs of particular concern are endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), which are known to interfere with hormonal changes and reproductive patterns in animals.15 While documentation in this field is in its infancy, one study involving participants from the United States, Canada, the UK, Greenland, Iceland and Denmark, provided information about EDC levels in the largest ever study of killer whales, and modelled that current concentrations could ‘severely deplete populations of killer whales in the most heavily contaminated areas within 30 to 50 years’. A single specimen was found to have polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) 100 times greater than the toxicity threshold for marine mammals.16

Further away from human activity, researchers of wild primates in the remote forests of Uganda have discovered nearly 100 chemical pollutants (including flame retardants) in the faeces of chimpanzees and baboons, most of which are known to disrupt the function of hormones in mammals.17 Such ECDs are a broad class of chemicals that are defined by their inadvertent ability to interfere with hormonal signalling, and include polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), phthalates (plastic softeners) and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) – the latter having been used as surfactants in cleaning products for several decades.

Household chemicals outside of this group, such as ammonium lauryl sulphate and sodium lauryl sulphate, are still common in products such as shampoos and toothpastes which although classed as a safe, can still cause moderate to severe skin and eye irritation – especially in children. The list of problematic chemicals identified by the Stockholm Convention has doubled since its enactment,18 but the number of new chemicals brought to market during the same period is now thought to be in the thousands or tens of thousands. Incredibly, many of these chemicals are introduced to achieve the same function as existing alternatives but are brought to market to circumnavigate conflicts of intellectual property.

End of life

While the challenges around the use and disposal of household chemicals are complex and widespread, packaging is also a major issue, with plastic containers for household chemicals accounting for a significant 9% share of the 2.5 million metric tons (or 90 billion pieces of plastic packaging waste) generated in the UK each year.19 Current global plastic production is expected to increase by a staggering 70% between 2020 and 2040,18 and the UK ranks a close second behind the USA for producing the most plastic waste per person than any other nation on the planet.

Lightweight packaging such as refill pouches remain problematic as soft plastics have a notably inferior end-of-life recycling infrastructure. Image © Olso

Recently, household chemical manufacturers have made efforts to ‘lightweight’ their packaging, by introducing refill pouches, using recycled materials or labelling packaging as recyclable – but such solutions remain problematic as most replacement materials have notably inferior end-of-life recycling infrastructures than their original counterparts, and simply continue to add to the plastic pollution crisis.

Most refill innovations therefore have limited benefit if consumers continue to rely on new single-use plastics to transport their purchase into reusable containers. However, an emerging resurgence in refill shops (where single-use plastics are eliminated) is an important model for reducing plastic dependency while also helping to invigorate communities and local high streets. Other moves to decouple plastic packaging from household products include innovations around plant-based materials, with household cleaning manufacturers such as Smol employing paper engineering and plastic-free packaging alongside compostable capsules for liquid detergents, while others such as Keep it Mack offer a hybrid of reusable packaging and plant-based concentrated cleaning products that can be rehydrated at home to reduce the impact of transport and packaging pollution. Alternatively Eco-mate claim to produce ‘the world’s first liquids in 100% plastic free paper bottles’ using sustainably sourced pulp waste as a by product of sugar cane production.

Home compostable and plastic-free packaging offers an innovative alternative to plastic pouches. Photo © Eco-Mate

Certification

Although regulations to help consumers identify the exact nature of household chemicals remain insufficient (even among the growing market of eco-labelled products), many manufacturers are moving towards active biobased ingredients obtained from microorganisms and plants, to replace fossil-based additives like surfactants and fragrance. Eco-labelling for such products remains voluntary but are usually independently verified.

EU Ecolabel This signifies minimal use of harmful chemicals or air and water emissions. Post-Brexit, an independent UK certification no longer exists, although items displaying the EU Ecolabel may still be traded.

Nordic Swan Ecolabel Primarily for the Nordic markets, the Nordic Swan Ecolabel ‘promotes resource efficiency, reduced climate impact, a non-toxic circular economy and conservation of biodiversity’ and considers raw materials, production, use, recycling and disposal.

Free-From Complex and unfamiliar chemical names and poor regulation around how ingredients are listed and labelled can make it difficult to understand the make up of a product. The following common but problematic chemicals are increasingly declared as absent in products, either by certification or labelling:

Parabens A preservative used to prevent the growth of bacteria and mould and increase shelf-life. Some parabens have been linked to endocrine disruption, while others such as butylparaben are considered of very high concern by the EU, but approved for use as a food additive in the U.S.

Phosphates Phosphates are commonly added to laundry products to help soften water. They have been linked to excessive growth of algae blooms in lakes and freshwater, which are responsible for reducing the oxygen levels vital for sustaining aquatic life.21 Their use is now limited to 0.3 grams per standard domestic dose in the UK and the EU, although they continue to be used extensively in agricultural fertilisers.

Phthalates Used for fragrance as well as softening agents in fossil-based plastics and have been linked to endocrine disruption, cancers and developmental issues for humans and animals, such as early puberty in girls. Some phthalates have been banned in the EU, but as the chemical ingredients of fragrances do not always have to be labelled,22 fragrance-free or non-synthetic fragrances are considered the best way to know they aren’t an ingredient.

Triclosan Used as an antimicrobial or antibacterial agent in cleaning products and has only recently been restricted by the EU but is banned in the US for use in liquid soaps.23 Classified as a pesticide and considered an endocrine-disrupting chemical in humans and animals, its widespread use may also cause bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents.