Macroplastics

Definition

Macroplastics are small pieces of plastic visible to the naked eye, measuring between 0.5–50 cm, which enter the environment as waste. Macroplastics are generally specified as one step up from microplastics although the sub-category ‘mesoplastic’ is sometimes used to define items between 5-25mm.

Production

Plastic pollution commonly occurs when plastics enter the environment and begin to break down into smaller parts. Macroplastics frequently start out as disposable or single-use plastics (SUPs), produced for very specific or supplementary functions such as packaging or industrial applications. Because macroplastics are low in value and small in size, it can be difficult to properly label or categorise them for recycling, and as such are more likely to be discarded as litter.

Due to their small size and weight, macroplastics are difficult to label for recycling and can easily leak into the environment. Photo © Olso

Although plastics provide an economical, durable and lightweight solution to many essential applications across modern society, these same functional properties mean discarded plastics take hundreds of years to break down, while contaminating ecosystems through chemical leaching. As a waste byproduct, macroplastics are particularly pervasive across a complex range of applications and sectors, from manufacturing and construction, through to fishing, agriculture and consumer goods.

Due to a surging recognition of the impact of plastic waste, many countries have begun to identify and eliminate both intentional and secondary macroplastic production, perhaps most famously with the banning of plastic drinking straws in the early 2020s. Although often politically derided as a token gesture, the removal of plastic drinking straws is part of a broader strategic global effort, including the UK Plastics Pact and European Single Use Plastics Directive. The pact initially identified eight ‘problem’ plastic items whose ‘use is avoidable or reusable options are available’.1 These include disposable plastic cutlery, plates, straws, plastic cotton-bud sticks and polystyrene food packaging – all of which have been found in various studies to be among the most pervasive and frequently identified items of macroplastic pollution – and have since been banned or restricted for sale in the UK to align with the European Directive.2

‘I don't think plastic is going to affect a shark very much, as they're munching their way through the ocean’. The U.S. President signs an executive order aimed at revoking single-use plastic restrictions, 2025.

In Use

As a classification, macroplastics form a bridge between larger ‘megaplastics’ (those greater than 50 cm that are more readily identifiable for capture, collection and sorting) and ‘microplastics’, which have gained significant media attention in recent years due to their now endemic presence throughout land and marine environments across the globe. However, because macroplastics are big enough to see and touch, they make up much of the litter or visual pollution in the human environment.

The ability to manufacture single-use plastics has enabled many industries to develop goods that are entirely reliant on macroplastics, either across supply chains, or for on-the-go consumption. Due to their size and nature, many macroplastics are also engineered to be easily detached from their counterparts, such as tamper-proof packaging components, security seals, caps and lids. Alongside plastic bottles, food containers, plastic cutlery and wrappers, this relatively narrow category of items are now believed to account for almost half of the human-made objects on a global scale.3

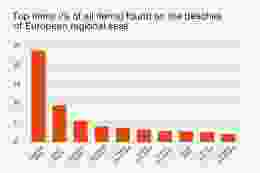

A citizen science survey published in 2024 by the European Environment Agency (EEA) recorded approximately 1.5 million items of litter along the coastlines and beaches of Europe, and found that plastic was ‘by far the predominant material’, accounting for more than 85% of total recorded items.4 Single-use macroplastics made up 52% of all collected litter, with ‘problem plastic’ cotton-bud sticks, straws, stirrers and polystyrene pieces among the top-ten items in all four of Europe’s regional seas. Carried out across more than 2,000 individual sites, the survey found cigarette butts (made of synthetic cellulose acetate) to be the most commonly identified item (23%), followed by macroplastic pieces (9.5%). Fortunately, other dominant items such as plastic drink caps now fall under EU rules on single-use plastics (adopted by the UK in 2024), that require plastic caps to be attached or tethered on all single-use plastic bottles.5

Source: European Environment Agency / European Topic Centre on Biodiversity and Ecosystems.

Studies suggest that littered plastic tends to stay within 160 km of the shore, due to the effect of tides and currents, which may explain why identifiable fishing-related items such as string and cord made up the lowest proportion of found objects in the survey (around 2.5% of all items), whereas soft plastics including crisp packets, sachets, sweet wrappers and plastic shopping bags accounted for 5.5%. Soft Plastics remain one of the most difficult to recycle plastics, and account for a significant 38% of plastic waste in the UK. This is especially true when used as part of a multi-material item or with other substrates – for instance, adhesive plastic tapes and labels, which often make it harder to recycle their partnered materials.

Another citizen science survey published in 2019 by environmental charity Thames21,6 found that the same macroplastics discovered by the EEA (food wrappers, cotton-bud sticks, takeaway containers etc) also accounted for nearly two thirds of all identifiable plastic waste on London’s river Thames, with wet wipes identified as the most common item – most of which contain plastic. Wet wipes often enter waterways via sewage overflows during periods of high rainfall,7 but unlike other macroplastics, wet wipes (or ‘sinking items’ such as sediment-filled plastic bags) are less likely to escape the river system. The Thames21 survey indicates that wet wipes are now responsible for physically changing the shape and sediment type of the Thames by accumulating in river bank mounds as large as 1,000 sq m, with a density as great as 200 wet wipes per sq m.8

Critics of attempts to reduce macroplastic pollution argue that a rising demand and consumption of plastic in Asia minimises the impact of western nations on global pollution. But a comprehensive 2019 report by The Ellen Macarthur Foundation, identified that although around 80% of ocean-bound plastic originates from Asia, 95% of the main plastics manufacturers are headquartered in USA and Europe.9 Therefore efforts to address the problem must start with the manufacturers responsible for creating plastic, and its model of consumption. This issue was highlighted perfectly in the 2024 Greenpeace campaign ‘Toxic Influence: The Dark Side of Dove’, which exposes how the British multinational corporation Unilever exploits the convenience of cheap single-use macroplastic sachets to sell small amounts of their products at more affordable prices in Southeast Asia.10 The campaign reveals that Unilever produce 6.4 billion of these macroplastic sachets each year – around 12,000 every minute, which are difficult to collect and almost impossible to recycle – yet remain largely unavailable in the Global North.

Macroplastic Waste fills a river in Navotas City, Philippines. Photo © Greenpeace

Environmental organisation Friends of the Earth take a strategic approach to tackling the impact of macroplastics, noting that ‘pointless’ or socially useless problem plastics should be phased out, whereas harder to replace or essential plastics with greater social value, such as used in hospitals and research settings, should only be retained for as long as necessary.11

End-of-life

Due to their small size and lightweight nature, it is easy for macroplastics to leak into the environment either from littering or by escaping waste management during waste collection – as evidenced on and around footpaths and pavements of populated areas, where they gather in undergrowth or become buried in topsoils. Regulated open landfill disposal and illegal dumping also allow rainwater and wind to transport macroplastics, which subsequently accumulate in gutters, drains and river systems on a downhill route to the sea. Figures vary, but it is estimated that as much as 2.4 million tonnes of plastic waste ends up in the oceans this way each year.12

In the late 1990s, a marine-based vortex was identified in the central North Pacific Ocean made up of around 80,000 tonnes of floating plastic waste. Now referred to as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, it covers an area of 1.6 million sq km – three times the size of France – with other examples identified in the South Pacific, North Atlantic and Indian oceans.13 Despite their size, only around 1% of the plastic waste estimated to enter the ocean each year is believed to end up in garbage patches, and more than 80% of their identifiable items are thought to come from the fishing industry. These human-made phenomena are indicative of the out-of-sight-out-of-mind challenges around macroplastic waste, which can entangle marine life, leach chemicals and break down into ever smaller pieces to create microplastic pollution, which is now known to be ingested across the food chain and back into the human diet through a process known as bioaccumulation.

Large-scale boom and trap systems developed to intercept macroplastic waste in rivers and seas. © The Ocean Cleanup

Non-profit organisations and charities such as The Ocean Cleanup have begun to implement large-scale boom and trap systems to intercept and collect plastic for recycling, and currently hope to remove 90% of floating ocean plastic by 2040. Although initially focussing on the The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, The Ocean Cleanup has recognised that plastic from land and rivers mostly congregates around coastlines and has begun extending its operations to rivers in countries including Indonesia, Guatemala and the United States, addressing the issue – quite literally – upstream.

However, modelling by institutions such as the University of Leeds Plastic Pollution Research project casts a more sombre tone, indicating that as demand for macroplastics increase over the next 20 years, ‘global capability to collect and safely manage plastic waste will decrease’. The project concludes that ‘whilst plastic waste generation is projected to grow exponentially, the capability of national and municipal governments to manage it effectively will be outpaced’.14