FSC

Definition

The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) is an international, non-governmental organisation that promotes the responsible management of commercial forestry. FSC operates the world’s most widespread voluntary certification system that covers over two million square kilometres of forest, and its logo is easily identifiable across the supply chain, from forestry management and logging, to manufacturing and end-use consumer products.

Principles

Established in the 1990s by a collection of environmentalists, businesses and community leaders, FSC now operates a certification system in over 80 countries that allows members to market products and services representing the organisation’s core values of (net) zero deforestation, fair wages and sustainability.

FSC certification confirms that a forest is managed in a way that both recognises biological diversity and benefits the lives of local people and workers. This ensures sustainable economic viability through a variety of principles, including high conservation values, workers rights and environmental and social impact monitoring.

FSC operations and certifications cover various stages of forestry production and produce, ranging from forest owners who wish to demonstrate that their logging is socially and environmentally beneficial, through to the chain of custody for companies that manufacture, process or trade forest products and wish to verify FSC certified forest goods along the production chain.

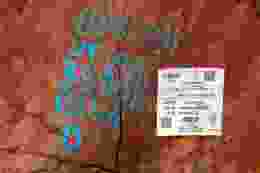

FSC lumber Identification labelling, Brazil. Photograph: Tarcisio Schnaider / Shutterstock

Implementation

In principle, if a material comes from a forest it can be FSC certified. The FSC label is now found across a wide range of products to verify that their raw materials were sustainably sourced. This range takes in viscose clothing, rubber in shoes, furniture, homeware and building materials, as well as recreational products, paper and packaging. Certification standards are built and developed from a local level (in places where sustainability policies may not yet exist), right through to regional and national levels and policy making.

Although the positive impact of certification is championed for its ability to define and set standards, third-party schemes like FSC have seen criticism when administered alongside or potentially against government-led legislation. Generally, legislation aim to embrace local differences between business cultures, stakeholders and costs across a country’s entire forest estate as opposed to individual sites and it has been argued that resulting issues, such as the doubling up of certification fees, can lead to a reduced take up of voluntary certification.1

In their 2021 report Destruction: Certified,2 Greenpeace identified FSC as ‘the most credible and effective forestry certification scheme’, but identified the organisation as ‘failing in terms of traceability and transparency’, indicating many reported cases of FSC certified companies or subsidiaries engaging in illegal logging, while suggesting that ‘FSC has also done little to stem the global tide of deforestation’.

Certification

For consumers, there are three types of FSC labels:

FSC 100% All materials used come from responsibly managed, FSC-certified forests.

FSC Recycled All materials are 100% recycled with no virgin wood.

FSC Mixed A mixture of materials from FSC-certified forests, recycled sources and controlled wood. Controlled wood isn’t fully certified, but originates from forests that are verified as low risk in terms of illegal logging and other unacceptable practices. Controlled wood is seen as a vital stepping stone to full FSC certification.

FSC consumer packaging labelling, UK. Photograph: Olso

As well as defining the material origins, FSC labels should also indicate product type (e.g. paper) and licence code, which can be used to identify the organisation holding the licence on the publicly accessible FSC database.

Greenpeace criticised FSC for its heavy reliance on mixing non-certified materials in FSC products, noting that across the industry, the variations between labels and certification are not always clear to consumers, who ‘typically distinguish only between products labelled as certified and those that are not’. Their report also suggests that companies using weaker schemes may ‘reap the same market benefits as those using stronger schemes, removing much of the incentive for investing in more robust certification’.